Readings:

Psalm 65

Isaiah 55:6-11

Revelation 21:1-6

John 3:31-35Preface of a Saint (3)

[Common of a Theologian]

[Common of a Scientist or Environmentalist]

[Common of a Pastor]

[For the Goodness of God's Creation]

[For Scientists and Environmentalists]

PRAYER (traditional language)

Eternal God, the whole cosmos sings of thy glory, from the dividing of

a single cell to the vast expanse of interstellar space: We offer thanks

for thy theologian and scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who didst

perceive the divine in the evolving creation. Enable us to become faithful

stewards of thy divine works and heirs of thy everlasting kingdom; through

Jesus Christ, the firstborn of all creation, who with thee and the Holy

Spirit livest and reignest, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

Eternal God, the whole cosmos sings of your glory, from the dividing of

a single cell to the vast expanse of interstellar space: We bless you

for your theologian and scientist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who perceived

the divine in the evolving creation. Enable us to become faithful stewards

of your divine works and heirs of your eternal kingdom; through Jesus

Christ, the firstborn of all creation, who with you and the Holy Spirit

lives and reigns, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

This commemoration appears in A Great Cloud of Witnesses.

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 9 Feb. 2019

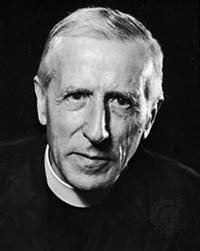

PIERRE TEILHARD DE CHARDIN

SCIENTIST AND MILITARY CHAPLAIN, 1955

Pierre

Teilhard de Chardin (May 1, 1881 - April 10, 1955) was a French philosopher

and Jesuit priest who trained as a paleontologist and geologist and took

part in the discovery of Peking Man. His theological and philosophical

works came into conflict with the Catholic Church and several of his books

were censured.

Pierre

Teilhard de Chardin (May 1, 1881 - April 10, 1955) was a French philosopher

and Jesuit priest who trained as a paleontologist and geologist and took

part in the discovery of Peking Man. His theological and philosophical

works came into conflict with the Catholic Church and several of his books

were censured.

Pierre Teilhard de Chardin was born in Orcines, close to Clermont-Ferrand, in France on May 1, 1881. When he was 12, he went to the Jesuit college of Mongré, in Villefranche-sur-Saône, where he completed baccalaureates of philosophy and mathematics. Then, in 1899, he entered the Jesuit novitiate at Aix-en-Provence where he began a philosophical, theological and spiritual career. Teilhard studied theology in Hastings, in Sussex (UK), from 1908 to 1912. There he synthesized his scientific, philosophical and theological knowledge in the light of evolution. From 1912 to 1914, Teilhard worked in the paleontology laboratory of the Musée National d'Histoire Naturelle, in Paris, studying the mammals of the middle Tertiary period.

Mobilised in December 1914, Teilhard served in World War I as a stretcher-bearer in the 8th Moroccan Rifles. For his valour, he received several citations including the Médaille militaire and the Legion of Honour.

In 1923 he traveled to China with Father Emile Licent, who was in charge in Tianjin of a laboratory collaborating with the Natural History Museum in Paris. Licent carried out considerable basic work in connection with missionaries who accumulated observations of a scientific nature in their spare time. Teilhard would remain there more or less twenty years. From 1926 to 1935, Teilhard made five geological research expeditions in China. They enabled him to establish a first general geological map of China. He joined the ongoing excavations of the Peking Man Site at Zhoukoudian as an advisor in 1926 and continued in the role for the Cenozoic Research Laboratory of the Geological Survey of China following its founding in 1928. During this time and after, he also made a great number of travels throughout the world, studying and lecturing.

Teilhard died on April 10, 1955 in New York City, where he was in residence at the Jesuit church of St Ignatius of Loyola. He is buried on what is now the grounds of the Culinary Institute of America, in Hyde Park, NY.

In 1925, Teilhard was ordered by the Jesuit Superior General Vladimir Ledochowski to leave his teaching position in France and to sign a statement withdrawing his controversial statements regarding the doctrine of original sin. Rather than leave the Jesuit order, Teilhard signed the statement and left for China. This was the first of a series of condemnations by certain ecclesiastical officials that would continue until long after Teilhard's death. The climax of these condemnations was a 1962 monitum (reprimand) of the Holy Office denouncing his works. It states:

"The above-mentioned works abound in such ambiguities and indeed even serious errors, as to offend Catholic doctrine... For this reason, the most eminent and most revered Fathers of the Holy Office exhort all Ordinaries as well as the superiors of Religious institutes, rectors of seminaries and presidents of universities, effectively to protect the minds, particularly of the youth, against the dangers presented by the works of Fr. Teilhard de Chardin and of his followers.".

Teilhard's writings, though, continued to circulate — not publicly, as he and the Jesuits observed their commitments to obedience, but in mimeographs that were circulated only privately, within the Jesuits, among theologians and scholars for discussion, debate and criticism. As time passed, it seemed that the works of Teilhard were gradually becoming viewed more favourably within the Church. However, the 1962 statement remains official Church policy to this day.

In his posthumously published book, The Phenomenon of Man, Teilhard writes of the unfolding of the material cosmos, from primordial particles to the development of life, human beings and the noosphere, and finally to his vision of the Omega Point in the future, which is "pulling" all creation towards it. He was a leading proponent of orthogenesis, the idea that evolution occurs in a directional, goal driven way, argued in terms that today go under the banner of convergent evolution. Teilhard argued in Darwinian terms with respect to biology, and supported the synthetic model of evolution, but argued in Lamarckian terms for the development of culture, primarily through the vehicle of education.

Teilhard makes sense of the universe by its evolutionary process. He interprets complexity as the axis of evolution of matter into a geosphere, a biosphere, into consciousness (in man,) and then to supreme consciousness (the Omega Point.)

Teilhard himself claimed his work to be phenomenology. Teilhard studied what he called the rise of spirit, or evolution of consciousness, in the universe. He believed it to be observable and verifiable in a simple law he called the Law of Complexity / Consciousness. This law simply states that there is an inherent compulsion in matter to arrange itself in more complex groupings, exhibiting higher levels of consciousness. The more complex the matter, the more conscious it is. Teilhard proposed that this is a better way to describe the evolution of life on earth, rather than Herbert Spencer's "survival of the fittest." The universe, he argued, strives towards higher consciousness, and does so by arranging itself into more complex structures.

Teilhard here proposed another level of consciousness, to which human beings belong, because of their cognitive ability; i.e. their ability to 'think', and to set things to purpose. Human beings, Teilhard argued, represent the layer of consciousness which has "folded back in upon itself", and has become self-conscious. So in addition to the geosphere and the biosphere, Teilhard posited another sphere, which is the realm of human beings, the realm of reflective thought: the noosphere. The noosphere has been compared to C. G. Jung's theory of the collective unconscious.

Finally, the keystone to his phenomenology is that because Teilhard could not explain why the universe would move in the direction of more complex arrangements and higher consciousness, he postulated that there must exist ahead of the moving universe, and pulling it along, a higher pole of supreme consciousness, which he called Omega Point.

Teilhard re-interpreted many disciplines, including theology, sociology, metaphysics, around this understanding of the universe. A main focus of his was to re-assure the converging mass of humanity not to despair, but to trust the evolution of consciousness as it rises through them.

— more at Wikipedia