Readings:

Amos 5:18-24PRAYER (traditional language):

Psalm 85:7-13

Galatians 3:22-28

Luke 1:46-55Preface of a Saint (2)

[Common of a Martyr]

[Common of a Prophetic Witness]

[Of the Holy Cross]

[For Prophetic Witness in Society]

O God of justice and compassion, who didst put down the proud and the mighty from their place, and dost lift up the poor and afflicted: We give thee thanks for thy faithful witness Jonathan Myrick Daniels, who, in the midst of injustice and violence, risked and gave his life for another; and we pray that we, following his example, may make no peace with oppression; through Jesus Christ our Savior: who with thee and the Holy Spirit liveth and reigneth, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language):

O God of justice and compassion, who puts down the proud and the mighty from their place, and lifts up the poor and

afflicted: We give you thanks for your faithful witness Jonathan Myrick

Daniels, who, in the midst of injustice and violence, risked and

gave his life for another; and we pray that we, following his example,

may make no peace with oppression; through Jesus Christ our Savior, who

lives and reigns with you and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

Lessons revised at General Convention 2024

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 10 July 2024

JONATHAN MYRICK DANIELS

SEMINARIAN (14 AUGUST 1965)

Jonathan Myrick Daniels was born in Keene, New Hampshire in 1939, one of two offspring of a Congregationalist physician. When in high school, he had a bad fall which put him in the hospital for about a month. It was a time of reflection. Soon after, he joined the Episcopal Church and also began to take his studies seriously, and to consider the possibility of entering the priesthood. After high school, he enrolled at Virginia Military Institute (VMI) in Lexington, Virginia, where at first he seemed a misfit, but managed to stick it out, and was elected Valedictorian of his graduating class. During his sophomore year at VMI, however, he began to experience uncertainties about his religious faith and his vocation to the priesthood that continued for several years, and were probably influenced by the death of his father and the prolonged illness of his younger sister Emily. In the fall of 1961 he entered Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, near Boston, to study English literature, and in the spring of 1962, while attending Easter services at the Church of the Advent in Boston, he underwent a conversion experience and renewal of grace. Soon after, he made a definite decision to study for the priesthood, and after a year of work to repair the family finances, he enrolled at Episcopal Theological Seminary in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in the fall of 1963, expecting to graduate in the spring of 1966.

In March 1965 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, asked students and others to join him in Selma, Alabama, for a march to the state capital in Montgomery demonstrating support for his civil rights program. News of the request reached the campus of ETS on Monday 8 March (my sources are a bit confused on the chronology of that week, but I think this is correct), and during Evening Prayer at the chapel, Jon Daniels decided that he ought to go. Later he wrote:

"My soul doth magnify the Lord, and my spirit hath rejoiced in God my Saviour." I had come to Evening Prayer as usual that evening, and as usual I was singing the Magnificat with the special love and reverence I have always felt for Mary's glad song. "He hath showed strength with his arm." As the lovely hymn of the God-bearer continued, I found myself peculiarly alert, suddenly straining toward the decisive, luminous, Spirit-filled "moment" that would, in retrospect, remind me of others--particularly one at Easter three years ago. Then it came. "He hath put down the mighty from their seat, and hath exalted the humble and meek. He hath filled the hungry with good things." I knew then that I must go to Selma. The Virgin's song was to grow more and more dear in the weeks ahead.

He and others left on Thursday for Selma, intending to stay only that weekend; but he and a friend missed the bus back, and began to reflect on how an in-and-out visit like theirs looked to those living in Selma, and decided that they must stay longer. They went home to request permission to spend the rest of the term in Selma, studying on their own and returning to take their examinations. In Selma, many proposed marches were blocked by rows of policemen. Jon describes one such meeting (ellipses not marked).

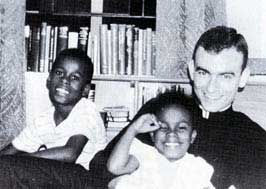

After a week-long, rain-soaked vigil, we still stood face to face with the Selma police. I stood, for a change, in the front rank, ankle-deep in an enormous puddle. To my immediate right were high school students, for the most part, and further to the right were a swarm of clergymen. My end of the line surged forward at one point, led by a militant Episcopal priest whose temper (as usual) was at combustion-point. Thus I found myself only inches from a young policeman. The air crackled with tension and open hostility. Emma Jean, a sophomore in the Negro high school, called my name from behind. I reached back for her hand to bring her up to the front rank, but she did not see. Again she asked me to come back. My determination had become infectiously savage, and I insisted that she come forward--I would not retreat! Again I reached for her hand and pulled her forward. The young policeman spoke: "You're dragging her through the puddle. You ought to be ashamed for treating a girl like that." Flushing--I had forgotten the puddle--I snarled something at him about whose-fault-it-really-was, that managed to be both defensive and self-righteous. We matched baleful glances and then both looked away. And then came a moment of shattering internal quiet, in which I felt shame, indeed, and a kind of reluctant love for the young policeman. I apologized to Emma Jean. And then it occurred to me to apologize to him and to thank him. Though he looked away in contempt--I was not altogether sure I blamed him--I had received a blessing I would not forget. Before long the kids were singing, "I love ---." One of my friends asked [the young policeman] for his name. His name was Charlie. When we sang for him, he blushed and then smiled in a truly sacramental mixture of embarrassment and pleasure and shyness. Soon the young policeman looked relaxed, we all lit cigarettes (in a couple of instances, from a common match, and small groups of kids and policemen clustered to joke or talk cautiously about the situation. It was thus a shock later to look across the rank at the clergymen and their opposites, who glared across a still unbroken "Wall" in what appeared to be silent hatred. Had I been freely arranging the order for Evening Prayer that night, I think I might have followed the General Confession directly with the General Thanksgiving--or perhaps the Te Deum.Jon devoted many of his Sundays in Selma to bringing small groups of Negroes, mostly high school students, to church with him in an effort to integrate the local Episcopal church. They were seated but scowled at. Many parishioners openly resented their presence, and put their pastor squarely in the middle. (He was integrationist enough to risk his job by accommodating Jon's group as far as he did, but not integrationist enough to satisfy Jon.)

In May, Jon went back to ETS to take examinations and complete other requirements, and in July he returned to Alabama, where he helped to produce a listing of local, state, and federal agencies and other resources legally available to persons in need of assistance. On Friday 13 August Jon and others went to the town of Fort Deposit to join in picketing three local businesses. On Saturday they were arrested and held in the county jail in Hayneville for six days until they were bailed out. (They had agreed that none would accept bail until there was bail money for all.) After their release on Friday 20 August, four of them undertook to enter a local shop, and were met at the door by a man with a shotgun who told them to leave or be shot. After a brief confrontation, he aimed the gun at a young girl in the party, and Jon pushed her out of the way and took the blast of the shotgun himself. (Whether he stepped between her and the shotgun is not clear.) He was killed instantly. Not long before his death he wrote:

I lost fear in the black belt when I began to know in my bones and sinews that I had been truly baptized into the Lord's death and Resurrection, that in the only sense that really matters I am already dead, and my life is hid with Christ in God. I began to lose self-righteousness when I discovered the extent to which my behavior was motivated by worldly desires and by the self-seeking messianism of Yankee deliverance! The point is simply, of course, that one's motives are usually mixed, and one had better know it. As Judy and I said the daily offices day by day, we became more and more aware of the living reality of the invisible "communion of saints"--of the beloved comunity in Cambridge who were saying the offices too, of the ones gathered around a near-distant throne in heaven--who blend with theirs our faltering songs of prayer and praise. With them, with black men and white men, with all of life, in Him Whose Name is above all the names that the races and nations shout, whose Name is Itself the Song Which fulfils and "ends" all songs, we are indelibly, unspeakably ONE.(NOTE: Much of Alabama has brick-red clayey soil. The region where the soil is black loam is called "the black belt." The term has no racial referent, although Yankees often assume that it does.)

(NOTE: Because Bernard of Clairvaux is remembered on 20 August, Jonathan Daniels is remembered on the day of his arrest, 14 August.)

SOURCE: The

Jon Daniels Story, ed. William J Schneider (Morehouse, 1992 ; ISBN:

0819215864 - out of print but should be available used) (orig. publ. 1967)

[Note: I highly recommend Outside Agitator: Jon Daniels and the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama, by Charles W. Eagles (Univ of Alabama Pr., 2000; ISBN: 081731069X). A documentary about him may be viewed online here.]