Readings:

Preface of Trinity Sunday

[Common of a Theologian and Teacher]

[Common of a Pastor]

[Of the Holy Trinity]

[For the Ministry II]

PRAYER (traditional language)

Almighty God, who hast revealed to thy Church

thine eternal Being of glorious majesty and perfect love as one God in Trinity of Persons:

Give us grace that, like thy bishop Gregory of Nyssa, we may continue steadfast in the

confession of this faith, and constant in our worship of thee, Father, Son, and Holy

Spirit, who livest and reignest now and for ever. Amen.

PRAYER (contemporary language)

Almighty God, who has revealed to your Church

your eternal Being of glorious majesty and perfect love as one God in Trinity of Persons:

Give us grace that, like your bishop Gregory of Nyssa, we may continue steadfast in the

confession of this faith, and constant in our worship of you, Father, Son, and Holy

Spirit, who live and reign for ever and ever. Amen.

Lessons revised at General Convention 2024.

Return to Lectionary Home Page

Webmaster: Charles Wohlers

Last updated: 11 January 2025

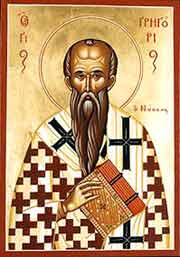

GREGORY OF NYSSA

(9 MAR 395)

Gregory

of Nyssa, his brother Basil the Great (14 June), and Basil's best friend

Gregory of Nazianzus (9 May), are known collectively as the Cappadocian

Fathers. They were a major force in the triumph of the Athanasian position

at the Council of Constantinople in 381. Gregory of Nyssa tends to be

overshadowed by the other two.

Gregory

of Nyssa, his brother Basil the Great (14 June), and Basil's best friend

Gregory of Nazianzus (9 May), are known collectively as the Cappadocian

Fathers. They were a major force in the triumph of the Athanasian position

at the Council of Constantinople in 381. Gregory of Nyssa tends to be

overshadowed by the other two.

Gregory of Nyssa was born in Caesarea, the capital of Cappadocia (central Turkey) in about 334, the younger brother of Basil the Great and of Macrina (19 July), and of several other distinguished persons. As a youth, he was at best a lukewarm Christian. However, when he was twenty, some of the relics of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste (10 March) were transferred to a chapel near his home, and their presence made a deep impression on him, confronting him with the fact that to acknowledge God at all is to acknowledge His right to demand a total commitment. Gregory became an active and fervent Christian. He considered the priesthood, decided it was not for him, became a professional orator like his father, married, and settled down to the life of a Christian layman. However, his brother Basil and his friend Gregory of Nazianzus persuaded him to reconsider, and he became a priest in about 362. (This did not affect his marriage.)

His brother Basil, who had become archbishop of Caesarea in 370, was engaged in a struggle with the Arian Emperor Valens, who was trying to stamp out belief in the deity of Christ. Basil desperately needed the votes and support of Athanasian bishops, and he maneuvered his friend Gregory into the bishopric of Sasima, and (in about 371) his brother Gregory into the bishopric of Nyssa, a small town about ten miles from Caesarea. Neither one wanted to be a bishop, neither was suited to be a bishop, and both were furious with Basil.) Gregory did not get along well with his flock, was falsely accused of embezzling church funds, fled the scene in about 376, and did not return until after the death of Valens about two years later.

In 379, Basil died, having lived to see the death of Valens and the end of the persecution. Shortly thereafter, Macrina died. Gregory was with her in the last few days of her life. Afterwards, he took to writing sermons and treatises on theology and philosophy. His philosophy was a form of Christian Platonism. In his approach to the Scriptures, he was heavily influenced by Origen, and his writings on the Trinity and the Incarnation build on and develop insights found in germ in the writings of his brother Basil. But he is chiefly remembered as a writer on the spiritual life, on the contemplation of God, not only in private prayer and meditation, but in corporate worship and in the sacramental life of the Church.

His treatise On the Making of Man deals with God as Creator, and with the world as a good thing, as something that God takes delight in, and that ought to delight us. His Great Catechism is esteemed as a work of systematic theology. His Commentary on the Song of Songs is a work of contemplative, devotional, mystical theology.

His book The Life of Moses is available from the Paulist Press in the series The Classics of Western Spirituality. The reader who is expecting a straightforward biography will be startled -- not necessarily disappointed. An example of his treatment is the following:

In Numbers 13 and 14 we read that when Moses had led the Israelites out of Egypt and to the borders of Canaan, he sent twelve spies into the land to look it over. They returned to report two things: (1) The inhabitants of the land were fierce warriors and would prove a formidable enemy. (2) The land was a good land, with fertile soil and an abundance of natural resources. As proof, they brought back a cluster of grapes so large that they hung it from a wooden pole that two men carried horizontally between them. Ten of the spies said that the enemy was too strong to be defeated, and that the Israelites ought to turn back, but the remaining two, Joshua and Caleb, urged the people to remember that the LORD was with them, and had shown Himself mighty to save. The people listened to the ten and prepared to turn back. At this the LORD was angry and said, "Very well, you shall wander in the wilderness for forty years, until all the men of this generation have died, except for Joshua and Caleb. Only then shall the next generation go in to possess the homeland that I promised to Abraham for his descendants." Hence the well-known child's nursery rhyme that goes in part:

Joshua the son of Nun and Caleb the son of Jephunneh

Were the only two who ever got thru to the land of milk and honey.

Gregory (following the example of the Apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 10) treats the Exodus as a type of our deliverance from the bondage of sin, and the Promised Land as a type of Heaven. He comments that the Israelites had been guilty of idolatry, of fornication, of repeated rebellions against Moses, of various disobediences to the commands of God, but that none of these moved God to deny them entrance into the Promised Land. It was only when they came to the Land, and God showed them what a good land He had prepared for them, and gave them a token of that goodness in the form of the cluster of grapes, hanging from a wooden pole between two spies, and they refused to trust in the promise of God to save them from their enemies, that they were turned back (indeed, that they turned themselves back). So, it is not failure to live virtuous lives that can keep us out of Heaven, but a refusal to believe in the mercy of God, and to trust His gracious declarations of His good will toward us, concretely expressed in the saving blood of Christ, Who is the True Vine, and Who for our sakes hung on the wood of the cross between two thieves, as the grape cluster hung on the wood of the pole between two spies, showing forth in His own Person the sign of God's good will to us and His assurance that He is ready to overcome all our enemies.

As you see, it is not really a biography of Moses, and it will not be to everyone's taste, not even to every Christian's taste. And even Christians who find this approach helpful will grant that it has its pitfalls. Clearly anyone who follows Gregory's example runs the risk of being led on a random walk by the will-o-the-wisp of his own imagination. But many Christians have received spiritual nourishment from this way of reading the Scriptures, and the example of St. Paul, as aforesaid, favors the view that this approach is at least sometimes of legitimate value.

by James Kiefer